Highpoint — the pair of celebrated apartment blocks set into the wooded slope of Highgate Hill — is one of the clearest statements of 1930s British modernism and a defining work by the émigré architect Berthold Lubetkin and his practice Tecton.

Commissioned in the early 1930s by the entrepreneur Sigmund Gestetner, the two phases of Highpoint were built as luxury flats that translated continental avant-garde ideas about light, plan and the social potential of housing into an English domestic scale.

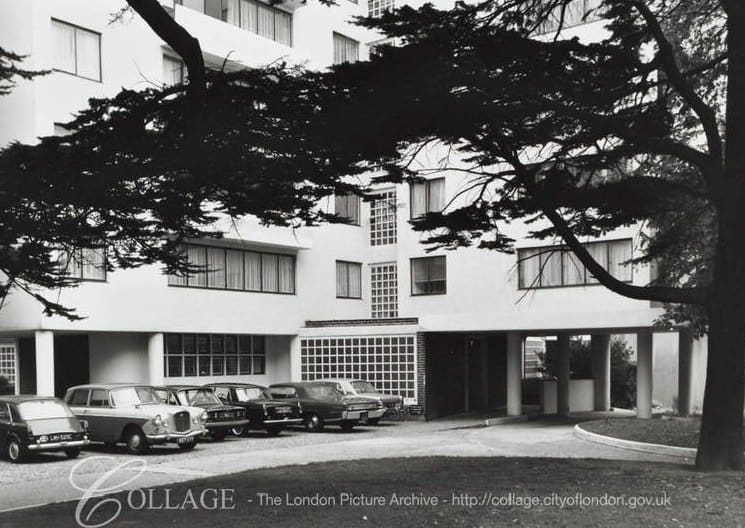

Highpoint I (often called Highpoint One) was designed and constructed between 1933 and 1935. It rises to seven or eight storeys in a cruciform plan that maximises daylight and cross-ventilation for each flat. Lubetkin organised the scheme around a carefully composed sequence of arrival spaces — a kind of promenade architecturale influenced by Le Corbusier — which turns the building’s entrance and communal rooms into theatrical, social spaces rather than mere service corridors.

The building was technologically ambitious for its time: reinforced concrete construction, attention to engineered detailing, and services that read as modern comforts rather than afterthoughts.

The success of Highpoint I encouraged Gestetner to commission a second block. Highpoint II followed between about 1936 and 1938 and is simultaneously a continuation and a refinement of the ideas tested in the first building. Where Highpoint I is pared back and white-rendered in the international style, Highpoint II introduces a richer palette of brick, tile and interior finishes — partly a response to climate and neighbourly complaints about the “dazzling” whiteness of the first block, and partly an expression of Lubetkin’s increasing comfort with a more expressive modernism.

Highpoint II also contains fewer but larger and more luxurious apartments, and Lubetkin himself took the penthouse — a potent statement of the architect living within his own social project.

From a domestic-technical standpoint the Highpoint flats were unusually well appointed for the 1930s: central heating, built-in refrigeration, laundry chutes and communal amenities such as a tearoom and a winter garden were part of the package, emphasizing comfort and convenience as much as modern style.

The arrangement of flats — the cruciform plan, the positioning of living rooms to follow the sun — shows Lubetkin’s pragmatic attention to everyday experience rather than ornament. The structural and engineering solutions were also notable; Ove Arup’s office was involved in devising methods for efficient concrete shuttering and other details that allowed ambitious forms to be achieved economically.

The architectural press quickly recognised Highpoint’s significance. Visitors such as Le Corbusier praised the scheme, and critics argued that Lubetkin had produced not merely an apartment block but a manifesto for a new kind of urban domesticity in Britain. Yet the buildings also provoked debate: some modernist purists were unsettled by the more classical and decorative touches that appear in Highpoint II (for example, the quirky use of caryatid figures supporting the porch), seeing them as a softening of doctrinaire functionalism. That tension — between rigorously stripped-down invention and a willingness to flirt with historical reference or luxurious materials — is part of what makes Highpoint interesting today.

After World War II Lubetkin and Tecton’s attention shifted increasingly to municipal projects, but Highpoint remained a standing demonstration of what high-quality private housing could be. The two blocks have survived both the changing tastes of the post-war decades and the pressures of development on London’s hillsides; they are now protected as buildings of exceptional interest and historical importance. Both Highpoint I and II are Grade I listed, a status that recognises their international significance and helps to ensure their conservation.

Today Highpoint is read in multiple ways: as an exemplar of interwar modernism in Britain; as evidence of Lubetkin’s belief that modern architecture could improve ordinary life; and as an early example of luxury apartment living that anticipated later London typologies. Conservation work over the decades has tried to respect original materials and proportions while upgrading services to contemporary standards, a familiar conservation challenge where a 1930s concrete shell must meet 21st-century standards of comfort, fire safety and insulation. Visitors and students of architecture still travel to Highgate to see Lubetkin’s work in the flesh — the building’s confident geometry, its airy communal spaces and its careful siting in the landscape still read as a persuasive argument for architecture that combines social intent with formal invention.

In short, Highpoint remains one of London’s clearest monuments to the interwar international style translated into residential form: technically inventive, socially ambitious and materially refined — and, nearly a century on, still an object lesson in how modernism was adapted, contested and domesticated in the British context.

If you’d like, I can turn this into a shorter brochure text, produce a timeline of key dates and people, or pull out illustrative quotations from contemporary reviews (I can fetch those primary sources next).

Leave a Reply